The origin of Series 1 Lenses and the Macro Zoom

Readers of this blog will know me as the system administrator for the Camera-Wiki.org web servers but I’m also a camera geek. One of my interests (or maybe obsessions) is learning about the history of Ponder & Best, more commonly known as Vivitar. You can read the full story of how I got started in my personal blog; see the post: Help Preserve Vivitar History! The short version is that I found an obscure Vivitar lens and, during the process of researching it, realized how little is known about the history of Vivitar.

I’ve been searching out old documents and records. I’ve also been collecting equipment. But the best source of authoritative information on the history of Ponder & Best has been talking with the people who worked there. Initially, I was just hoping to improve the Vivitar pages on Camera-Wiki.org but I’ve learned so much that I’d like to start sharing it with others through a series of posts on our blog. To start out, I’d like to introduce one of the Ponder & Best employees I’ve been communicating with.

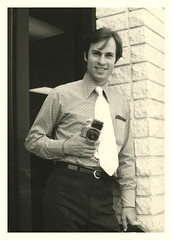

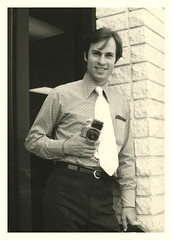

Bill Swinyard at P&B building on Pico Blvd in West LA

Bill Swinyard joined Ponder & Best in early 1969 and was with the company through late 1971. He started work at the P&B building on Pico Blvd. in West LA and left P&B shortly before its move to new offices in Santa Monica, CA. Bill was Brand Manager in the marketing department. His responsibilities encompassed all of the Vivitar lenses and lens accessories, then about 60% of Vivitar’s sales. He was involved in marketing research, market development, packaging, pricing, advertising, publicity, and dealer and sale force communications.

After leaving P&B, Bill went on to Stanford University for a PhD and then became a professor of marketing. He has been on the faculties of the National University of Singapore, Arizona State University, Santa Clara University, and Brigham Young University. Now retired, Bill continues his lifelong interest photography and also does some very nice woodturning, two subjects you can learn more about on Bill’s website, Snap Shavings.

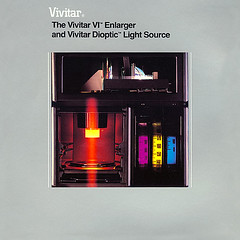

Vivitar Series 1 70-210mm f/3.5, the first Series 1 lens. Photo by flickr user C. Strife

While at P&B, Bill had a hand in new product development and was central to the start of the Vivitar Series 1 lens program, which is where today’s story starts. Most accounts of the Series 1 lenses you’ll find online say simply that they were designed by Ellis Betensky to Ponder and Best’s specifications. As you might have guessed, there’s a lot more to the story. I’ll let Bill pick it up from here:

“I was the brand manager in charge of marketing (and initially, development) of the Series 1 lenses, and it actually started not with Ellis Betensky, but with two P&B research guys (Gary Eisenberger and Murray Schwartz) and myself. Betensky was called in later, to some regret.”

“Vivitar had some very smart and motivated people in the early ’70s and let them lead out. We became very good at introducing innovative products during a time when 35mm SLR sales were booming. As long as we produced sales, we had free access to the budget. We also had a talented and funky ad agency that was willing to advance outlandish — sometimes outrageous — ideas, which propelled our sales beyond our forecasts.”

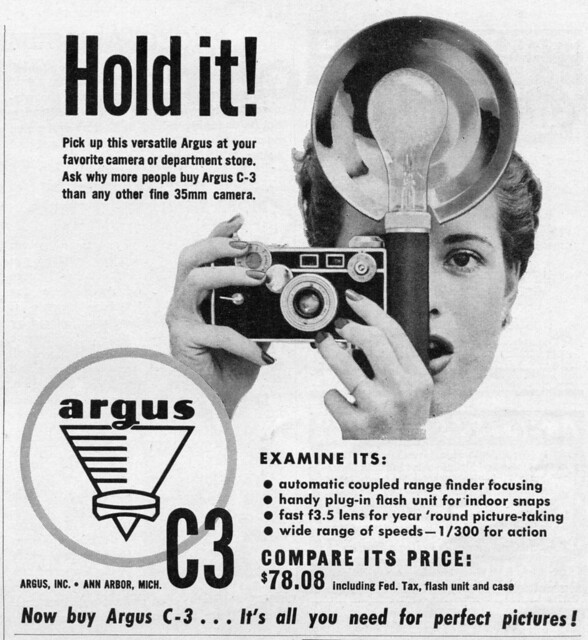

An example of P&B's creative advertising

“In 1970-71 I was working steadily with Gary Eisenberger and Murray Schwartz on all kinds of new ideas for lenses. Neither Gary nor Murray was an engineer nor designer but they were astonishingly smart and imaginative. In one aha moment we were examining an unsolicited prototype super-8 movie camera that had a little switch on the lens. You’d push a button and turn a lens collar a bit. Move this switch and, wow, it would macro focus right down to an ant crawling on the front element of the lens!”

“I suggested that Gary and Murray tear the lens apart to see how the macro function worked. It was a result of one internal lens element that shifted. We’d never seen anything like this. Previously, macro focusing had all been about lens extension, not moving shifting internal glass. Together we wondered if it were possible to use this method to create a macro-focusing 35mm lens.”

“The manufacturer of the movie camera was not helpful, saying that the shifting internal element had been an accidental discovery that worked only with a tiny image. In our aftermarket consumer-lens world of the time, 35mm lenses were based on established design principles and optical parameters having relatively simple lens element groupings. Most Vivitar designs were micro-theoretical improvements to the well-known European lens designs.”

“Now this was the computer mainframe era, and computer time was accessible only to the largest companies or universities, or to smaller firms on a time-shared basis. Time-share computer time was expensive and neither Vivitar nor its suppliers knew about designing consumer lenses with mainframes. So our lenses were designed by hand calculation and desk calculators, followed by much trial and error. Thus our new lenses were based on classical optical designs, which had taken many months or even years of work, followed by extensive tests on prototype after prototype, to get right. We knew that none of our lens suppliers was up to the job of this crazy macro-zoom project, and we thought it would be unlikely — maybe impossible — for Vivitar to tackle the project on its own.”

“However, I approached Bruce Shomler (then our Sr. Marketing VP) about our idea and the three of us showed him the macro feature on the movie camera. We explained how it worked. He became very excited. He brought us into Jay Katz’s office (the Executive VP; Jay had hired me) and we repeated the pitch.”

“Meanwhile, our annual national sales meeting was coming up, and for it I was making a demo movie using that prototype movie camera. In one scene I had ants crawling on the surface of the front element; in another I pressed my fingertip against the lens. The film showed both in crisp focus. I showed the film at the sales meeting. The sales force of 55 people laughed and cheered when they saw the macro feature demonstrated. The sensation of this presentation brought Jay Katz back into the mix.”

“A few days later, Bruce Shomler had me make a presentation to senior management (Bruce, Jay Katz, John Best, Paul Ellis [who later founded Kiron]) about what the consumer research showed; what zoom lens features and ratios would be marketplace killers. I summarized that lens weight and size were relatively unimportant (amateur photographers of the day loved the look of big cannons). Anti-reflective multi-coatings were essential. The most successful zooms would feature a single-collar zoom design. And most important, they would come in long-stretch focal lengths having popular fields of view: first a 70-210mm, next a 35-85mm. Or instead of the 35-85mm, a 35-105mm or even better a 35-135mm. I presented the last two ideas facetiously because I knew they were impossible. But nobody laughed, and I wondered why.”

“But then I learned that Ellis Betensky (Opcon Associates) had already been approached by these senior managers for design help on a new lens line. Using Vivitar’s design parameters he soon began development of our 70-210 macro-focusing zoom using his new auto-optimizing design software.”

“In use, Betensky would input the program with hundreds of data points; e.g. glass refraction and coatings data tables, lens curvature limitations, acceptable aberration characteristics, dimensional information, focal length tables, which or whether any lens elements could move, etc. Dozens of computer hours later an optical design would be generated. Then he’d examine the output, polish his inputs and enter the data anew. This went on for over six months. Vivitar had an agreement with Betensky about his billing fees. We thought this also included computer time.”

“We knew Bentensky was brilliant. But we didn’t know his muscular mind was not matched by common sense, for it seemed he had completed our contract without involving the owners of his computer time. Finally he presented us with the design for the first 70-210mm Auto-Optimizing Macro-focusing Zoom Lens. And Perkin-Elmer presented us with a bill for computer time of $1M (in 1971 dollars – equivalent to $5.7M today!), and a claim of copyright infringement for using their intellectual property. Vigorous negotiations followed.”

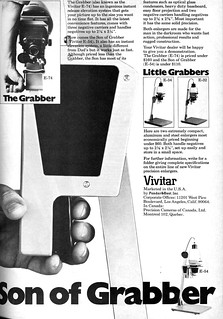

Ad for the first Vivitar Series 1 70-210mm f/3.5 Macro-focusing zoom lens

“This first Vivitar Auto-Optimizing lens became the Vivitar Series 1, in a single-collar or one-touch design. It had staggering complexity, having 15 optical elements in 10 groups, and required delicate final hand assembly and tuning. It was only one lens, but it was to be the first of a pro-quality lens line with an amateur’s price range. The 70-210mm was a delicious piece of work. Gorgeous, smooth, beautifully machined, and having impressive optical performance. And that macro! That was the deal-breaker.”

“I left Vivitar for Stanford even before the first prototype was delivered. But while I was a PhD student Jay Katz sent me a gift — one of the early production versions of the lens. The following summer I visited the Vivitar offices where Jay Katz saw me and shouted, “it’s Bill Swinyard the developer of the Series 1 lens!” Hyperbole of course, because many people had been deeply involved, especially Gary Eisenberger and Murray Schwartz. And … well, Ellis Betensky.”

“Incidentally Gary soon left Vivitar for a family photo business in New York, and Murray used his Vivitar contacts to open an art-glass design shop in Venice, California. Many of his creations used multi-coated lens-filter glass shards or imperfections. In direct light his creations continually changed colors and made a sensational impact.”

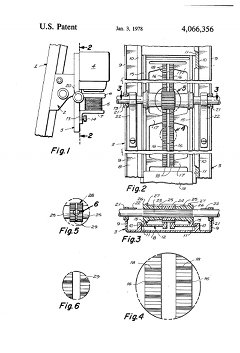

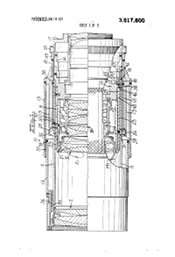

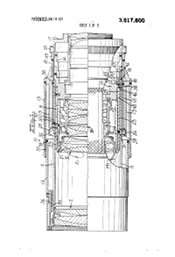

Patent 3,817,600 Zoom lens having close-up focusing mode of operation

In 1974, a couple of years after Bill left the company, the United States patent office granted P&B patent number 3,817,600 for a Zoom lens having close-up focusing mode of operation. The 1972 application lists Rénzo Wantanabe (an engineer at Kino Precision in Japan) and Ellis I. Betensky of Stamford, CT as the inventors. This patent is referenced in later macro-focusing zoom lens patents by Canon, Nikon, Minolta, Sony, Carl Zeiss, Nippon Kogaku, and Robert Bosch GmbH.

So next time you use a modern macro zoom lens, remember to thank the inventive folks at Ponder & Best; because every macro-zoom lens around today traces its heritage back to the Vivitar Series 1 70-210mm f/3.5 and the day Bill, Gary, and Murray wondered if a serendipitous feature on a prototype 8mm movie camera could be applied to 35mm lens design.

I’ll be posting more stories of Vivitar history here in the near future. If anyone reading this was a Ponder & Best or Vivitar employee and would like to share stories of the company’s history or help me in my research, please contact me. If you enjoyed hearing about this research or other research done by Camera-Wiki.org’s many editors, please consider making a small donation to help us pay for hosting and maintenance. We’re all volunteers and rely on your support to keep things going.