Vivitar Re-invents the Enlarger

In my last Vivitar historical article, I told the story of Ponder & Best‘s re-invention of the zoom lens when they introduced the Vivitar Series 1 70-210mm f/3.5 Macro Zoom. The company also successfully re-invented the flash with the Vivitar 283 and later the Vivitar 285, considered classic workhorses by strobe users for over a decade. In the 1970s Ponder & Best tried with less success to re-invent the enlarger. The pinnacle of this effort was the Vivitar 356 Dichroic Enlarger.

While my primary interest is in Vivitar lenses, two ex-Vivitar people brought this interesting story to my attention. The most significant discovery was a collection of photos taken at the enlarger factory by Gordon Lewis. You may recognize Gordon’s name from the acknowledgements page of the 1981 book on Vivitar’s products, The Vivitar Guide by John C. Wolf. Vivitar was only a small part of Gordon’s fascinating story, which he summarizes:

I started at Vivitar as a consumer relations correspondent in 1975 or ’76. I was eventually promoted to Marketing Communications Specialist. I left Vivitar to become Mgr. Marketing Communication at Kiron, a spin-off company led by ex-Vivitar execs Paul Ellis and Richard Wolfe. I was there for roughly two years, after which I made a radical career change: I became a sitcom writer. My show credits include Amen, Family Matters, and In Living Color. After tiring of the insecurity and absurdity of Hollywood, I made another career change. I’m now an instructional designer who specializes in web-based training for Fortune 500 clients. I have a photography blog (Shutterfinger) and a photography portfolio on Zenfolio.

Gordon has been immensely helpful in several areas of my Vivitar research. Expect to see more from him in the future including more behind-the-scenes photos of Vivitar.

The second piece of the enlarger puzzle fell into place during an email exchange with Peter D’Arpix, who did the product photography for Vivitar’s TX lens brochures and shot the original product photos of the first VI Enlarger.

Finally, I’d like to thank James Ollinger, who provided scans of several Vivitar enlarger ads and whose very complete website, Ollinger’s Guide to Enlargers was enormously helpful to me in filling in missing details of this story.

Ponder & Best began selling enlarging lenses in the 1960s but these lenses were not well received. It’s not known who made these early Vivitar enlarging lenses but to this day they are considered far below average in quality. In entering the enlarger market, P&B faced two challenges; offering improved quality lenses and coming up with an enlarger that embodied the same kind of revolutionary technology improvements as the Series 1 lenses.

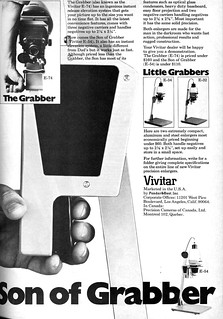

Around 1971, P&B introduced the E series enlargers. These included the E-32, E-33, E-34, E-36, E-54, and E-74. Four of these (the E-32, E-34, E-54, and E-74) included an innovation that replaced the usual rack-and-pinion column adjuster. With a typical enlarger, one moved the head up and down by slowly rotating a knob that turned a gear interlocked with a track on the enlarger column. The E series introduced a large squeeze handle that Vivitar called a “grabber”. Squeezing the handle unlocked the head and allowed the user to lift or lower it to the desire position. Releasing the grabber locked the head into the new position.

This resulted in the marketing company promoting grabber-based nicknames for each of the enlargers. The E-74 became known as “The Grabber”. The E-54 was called “Son of Grabber”. The E-34 and E-32 were called “Little Grabbers”. The E series enlargers received fairly good reviews in major photography magazines, earning points for rigidity, smooth movements, and evenness of lighting. The minor innovation of the grab-handle was not viewed as much of an improvement over traditional enlargers however and the E series as a whole were seen as little more than good quality, low-cost options for beginners.

At the same time P&B began offering a new series of enlarging lenses made by a “well-known and respected Germany optical company”. Some say this was Rodenstock Photo Optics, maker of the Rodegon enlarging lenses. Others say it was Schneider Kreuznach, maker of the Componon enlarging lenses. The serial numbers for these lenses begin with 13xxx. Based on what’s known of Vivitar manufacturer serial numbers, this seems to support Schneider Kreuznach as the maker.

In 1978, after a few years of experience with the E series, P&B was ready to go all out. Or perhaps we should say Vivitar was ready to go all out because it was in this time period that Ponder & Best officially changed their name to Vivitar Corporation. They would roll out their idea of the ultimate enlarger in two steps, the first being the Vivitar VI and the second being the Vivitar 365. Vivitar also did something they’d never done with their lens lines; they not only designed but also manufactured these two enlargers at a factory in the United States. Next time you hear someone say “Vivitar never made anything themselves” remind them about the VI and 356 enlargers. Gordon Lewis, who visited the Vivitar enlarger factory and took the photographs included here, recalls this about the factory:

As I recall, it was a Vivitar facility in Inglewood, CA. The Vivitar VI and 356 enlargers were assembled exclusively by Vivitar. They also assembled some sort of daylight darkroom contraption that looked sort of like a funnel-shaped box. The widest part of the funnel was the base. The narrow part had a color enlarger head.

I’d be interested in hearing from anyone who has photos or more information on this strange-sounding daylight enlarger. Could this mystery device be the Vivitar Polaroid Slide Printer?

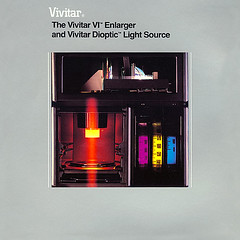

One of the biggest problems with enlargers is heat build up in the negative from the light source. The light source of an enlarger of that era was a big, high-powered light bulb that generated huge amounts of heat. A lot of that heat was transferred to the negative and during a long exposure negatives could buckle, burn, or melt. Even if the heat wasn’t sufficient to damage the negative it could still cause it to “pop” – to suddenly flex in one direction or the other altering the focus. The traditional solution was to put filters in place to reduce IR transmission but heat transfer was still possible due to the proximity of the bulb and negative.

Vivitar’s unique solution to the heat problem was the “dioptic light source”. The light source itself was quartz halogen lamp. The light passed through a IR reflecting filter, then through cyan, magenta, and yellow dichroic filters. It was then reflected 90 degrees by a mirror into a light pipe made from optical glass or acrylic that carried the light but not the heat the remaining distance. The result? The light pipe acted as an almost perfect insulator, transmitting effectively no heat to the negative. Modern Photography’s August 1978 review of the Vivitar VI enlarger offered this praise for the light pipe:

Temperature at the negative tests were amazing:

Time (sec) Temp.(°C) 0 18 30 18 60 18 Absolutely no heat was transmitted from light source to negative! None! Zero! The light pipe proved to be an extremely effective heat insulator–the best we have ever seen.

the Vivitar Dioptic Light Source performed beautifully. Exposures were fast, even with heavy filtration, and images were crisp and well saturated, indicating effective infra-red and ultraviolet filtration.

The Vivitar 356 improved further on the VI by moving the integrated power supply to a separate unit, reducing the weight of the head.

Vivitar took the enlarging lenses to the next level as well, releasing the Vivitar VHE enlarging lenses. Like their predecessors, these were 13xxx serial numbers lenses made in Germany, presumably by Scheider Kreuznach (though a persistent minority can still be found supporting Rodenstock as the maker). These lenses were comparable to the best quality German enlarging lenses. Some modern users claim the internal parts of the VHE lenses can be swapped directly with Schneider Kreuznach’s Componon lenses of the same vintage.

For marketing, Vivitar contracted with Henchy/Kay. Peter D’Arpix, the photographer on the project, received one of the first VI enlargers:

The enlarger arrived from the studios of the TV ad production company, scuffed up and with one control knob missing as well as some screws. So I had to switch out screws and knobs as I turned the different faces to the camera. Such fun! I worked I think with Rusty Kay. This was before Photoshop, so the “light paths” were created with multiple exposures of the 4×5 undeveloped film in the camera with many tests! But all done eventually on one sheet of film.

As they’d done with Vivitar’s TX Lens series, Peter and the Henchy/Kay team produced an excellent quality brochure to help market the new enlargers. Vivitar also introduced full-page advertising in major photography magazines for both enlargers.

Vivitar’s enlarger story doesn’t reach the same happy ending as the Series 1 lens and flash stories. It’s hard to say for sure why the enlargers weren’t more successful but Peter’s experience with the enlarger knobs foreshadows problems that would continue to plague the products. One contributing factor is no doubt the bad reputation of early Vivitar enlarging lenses. Despite the high quality of the Vivitar VHE lenses, they continue to be regarded as sub-standard by modern collectors based solely on the reputation of their predecessors.

Another thing that hampered success was an innovation included in the VI and 356 enlargers; the negative carriers. Most enlargers use a negative carrier made from pieces of flat metal. They’re sturdy, cheap, and you can even construct one yourself if needed. The Vivitar enlargers used a plastic negative carrier. It was a clever design with a circular ridge on top that interlocked with a ridge on the condenser housing. It provided a great fit while allowing the carrier to rotate 180 degrees. This sounded great in theory but in practice they could be hard to find and a Do-It-Yourself carrier was out of the question. And re-using carriers from other enlargers was impossible.

Even the innovative light source was not without problems. The diameter of the light pipe seems to have been chosen with 35mm negatives in mind. It produced very consistent lighting in that use. But with large format negatives there could be significant light falloff at the edges. Combined with vignetting on the negative from the taking lens, it took some work to get an acceptable print.

Gordon Lewis summarizes the problems:

[What] I remember about the fiber-optic light source was that it did not radiate any heat and therefore would not cause negs or slides to “pop” during focus or exposure. Unfortunately, because of its relatively small diameter, it caused vignetting with medium format film. It was great for 35mm though. Two more things: Most users didn’t like that the neg and slide carriers were plastic; also, the enlargers were not a sales success. Neither were the Vivitar VHE-branded enlarging lenses.

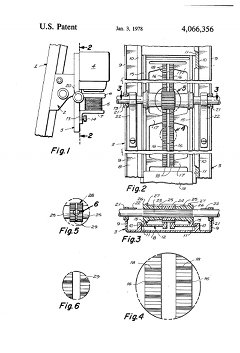

While Vivitar did not achieve the same success with their Enlargers as they did with the Series 1 lenses, they did achieve a lot of unique innovation in the field. Their work resulted in a string of patents including Patent number 4,066,356 in 1978 for an Anti-Backlash Means for Adjusting Enlargers, invented by John C. Parker (note that the last three digits of the patent are 356 – could this be the source of the Vivitar 356 Enlarger’s name?); Patent number 4125315 in 1978 for a Light Mixing Device, invented by Michael F. Praamsma; Patent number 4129372 in 1978 for a Light Mixing Apparatus and Photographic Enlarger Emobodying Same, invented by Michael Allgeier; and Patent number 4274131 in 1979 for a Light Diffusing Means for a Photographic Enlarger, invented by Michael F. Praamsma. All of these inventions were later adapted or referenced by other companies for new technologies used in enlargers, photocopiers, and scanners.

I’ll be posting more stories of Vivitar history here in the near future. If anyone reading this was a Ponder & Best or Vivitar employee and would like to share stories of the company’s history or help me in my research, please contact me. If you enjoyed hearing about this research or other research done by Camera-Wiki.org’s many editors, please consider making a small donation to help us pay for hosting and maintenance. We’re all volunteers and rely on your support to keep things going.

10 Responses to Vivitar Historical Research: Part 2